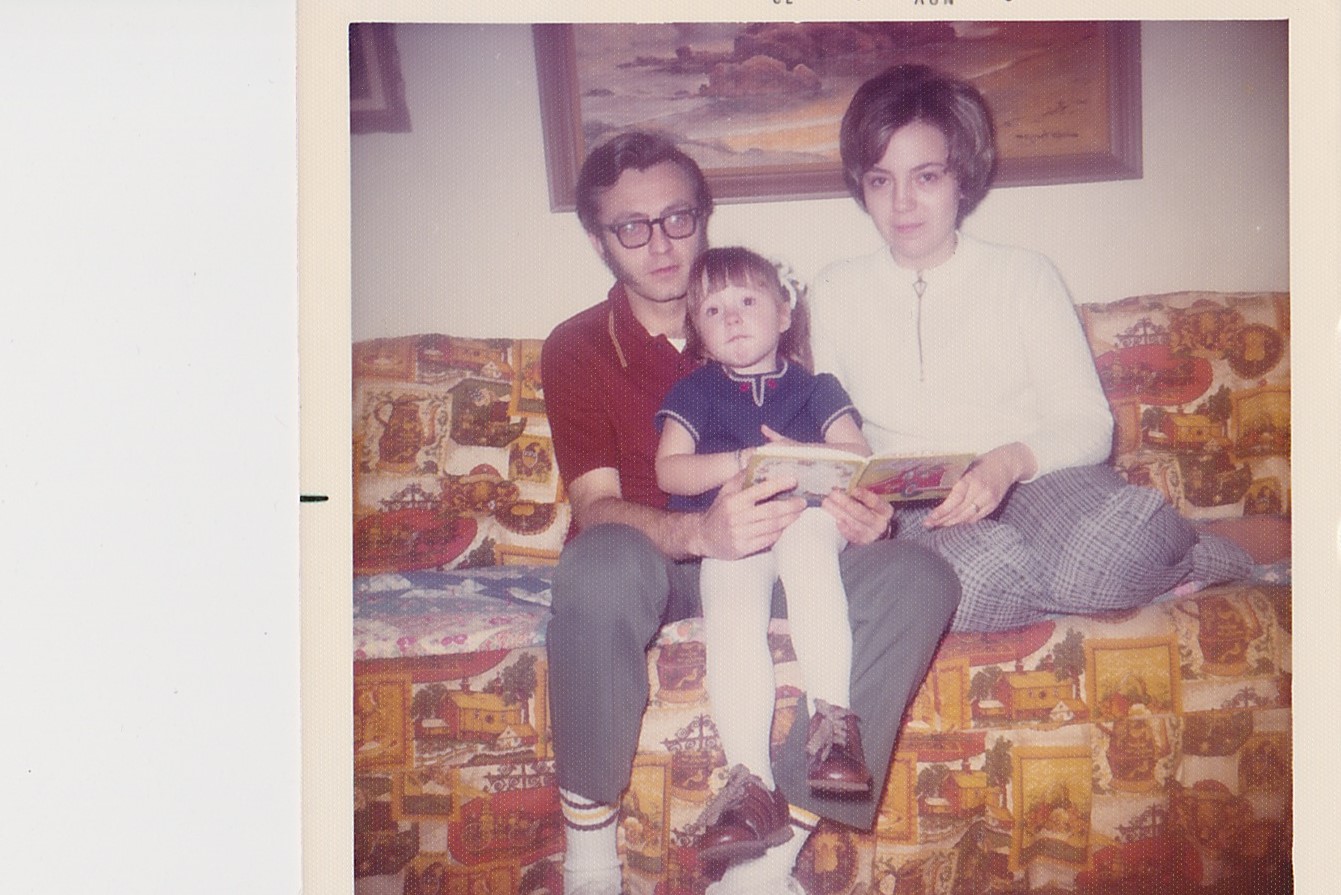

Of all the things I lost in 2020—including my wedding, my honeymoon, and my faith in America and in people in general—I miss my dad the most.

I miss his stillness. His quietness. Really, I miss his famous Dyer Reserve, which I inherited, for better or for worse. That reserve is, I suspect, partly a simple preference for our own company—life is easier for some of us when we’re alone. Few people understand the Reserve for what it really is, and it does make it harder to get to know us.

When I was little, my Dad would sit on the edge of my Sears canopy bed every night to say goodnight. To keep his attention and time, I’d ask random question after random question. Daddy, how are pill bottles made? Why does it snow? How do airplanes fly? He’d always take the time to answer, often with words far above my 7-year-old head. But it didn’t matter, because he was there with me, really there.

Dad worked long hours, like a lot of men in his generation. I knew it was Saturday when he went to work an hour later than normal, and in a polo shirt and jeans rather than a suit and tie. He wasn’t an easy person to be close to. I always wanted more of him, always a little intimidated by him. He was the smartest man in the world.

In my 20s, I went through the usual young adult Angry At My Parents phase, which gives me painful stabs of regret when I think about it today. But in his final years, we grew closer, especially after we kids bought him an iPad and we could text him regularly on it. Perhaps he liked the iPad because it gave him time to think about what to say. Through those texts, I was regularly reminded of how in-touch with the world he was, even in his late 70s. And how wise. And on his part, he loved reading texts from his kids and seeing photos of our trips. Mom said he was never more excited than to get our cheesy tourist photos from England. He printed them out on regular paper on his home printer. Later he’d tell me he’d always wanted to visit England, but his breathing had deteriorated so badly in his final years that flying was out of the question.

Few people took the time to sit and talk with my dad, but those who did were in for a treat. He had interesting stories, could quote baseball statistics like an almanac, and would surprise you with his insight and kindness.

He fell very sick in January 2020. It’s not impossible that he had COVID-19, but there’s no way to know for sure, and he had enough things wrong with him that any one of those could have taken him from us.

The last time I saw him, in a nursing home in Des Moines, he wasn’t fully conscious. Wake up, Daddy, I wanted to scream, feeling panicky and confused and little. He had just been moved to hospice a couple of days before, and we didn’t know how long he had. I had this strange idea that hospice would free him, and then he’d be OK, for a while. Grief made me believe things that made no sense.

He looked peaceful that night for the first time in months. He was breathing calmly and seemed to be sleeping. Maybe it’s only in books that people know the right thing to say at a moment like this.

“Daddy, I got my wedding dress yesterday. It’s pretty. I’m going to keep your name. I’ll love you forever,” is what I said. Then I bent and kissed his forehead. His spirit shimmered, then I felt rather than saw his spirit rise to meet me.

I ran out of the room and down the stuffy nursing home hall, shocked and sobbing.

The next morning, my brother called to say he’d passed. My mother was holding his hand. “Go find Mom,” she’d said, her way of letting him go to reunite with his beloved mother-in-law. Then he was gone.

Losing him felt like being pushed off a swing at its highest point, that place and time when your stomach starts to fall away. I felt rage about his suffering and sorrow about his passing, and these feelings endured for months. My grief was both inhibited by and exacerbated by the fear and stress of the pandemic. I was out of control.

A few months later, we eloped on my birthday in June, hoping that doing something beautiful would break the dark spell and help me feel OK again.

It helped. I married the very best of men, a man who’s also quiet and strong and patient with me. The wedding dress still hangs in my closet, waiting to be worn in a real wedding, one without my dad.

Today, a year later, I still cry. I’m overly sensitive to anything resembling a loss, and I fall off-center too often. But I feel him with me every day, and when the grief gets too strong, I see him shaking his head and holding up his hands, telling me not to go there. That I’m to go forward and be happy. And that he’s watching and waiting, quietly.